Can you name five women artists? It's surprisingly difficult for most people, even more so if you leave out the big three: Mary Cassatt, Frida Kahlo, Georgia O'Keeffe. This March, for Women's History Month, the National Museum for Women in the Arts (NMWA) is leading a social media campaign to share stories of women artists using the hashtag #fivewomenartists. I'm doing my part by sharing this list of five great picture books about women artists. Not including Cassatt, Kahlo, or O'Keeffe, although there are some gorgeous picture books about them, too!

Louise Bourgeois, M is for Mother, 1998, pen and ink with colored pencil and graphite, National Gallery of Art, Washington

Cloth Lullaby: The Woven Life of Louise Bourgeois by Amy Novesky; illustrated by Isabelle Arsenault (Abrams, 2016). As a child, 20th-century artist and sculptor Louise Bourgeois learned to weave and repair tapestries alongside her mother in the family's tapestry restoration workshop. This experience inspired some of her most powerful works, including a series of steel spider sculptures--the largest of which is called Maman.

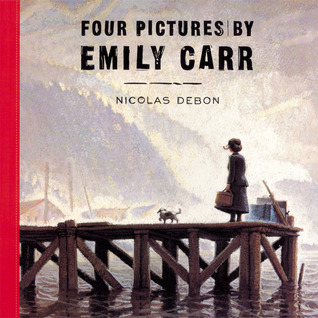

Four Pictures by Emily Carr by Nicolas Debon (Groundwood, 2003). Emily Carr (1871-1945) is one of Canada's most renowned artists; her work is now exhibited with and compared to Kahlo's and O'Keeffe's. In this graphic novel, Debon traces Carr's life story through four of her best paintings (also reproduced here).

Summer Birds: The Butterflies of Maria Merian by Margarita Engle; illustrated by Julie Paschkis (Henry Holt, 2010). I interviewed Margarita about this book when it first came out six years ago, and I still love it. Told in the voice of the young Maria Merian, 17th-century Dutch artist and naturalist.

Beatrix Potter and the Unfortunate Tale of a Borrowed Guinea Pig by Deborah Hopkinson; illustrated by Charlotte Voake (Shwartz and Wade, 2016). Spoiler alert: the guinea pig DIES. But if you can get past that, this is a charming book, and the picture-letter format is similar to how Beatrix Potter's own early stories were written. There's even a P.S. (the author's note).

Stand There! She Shouted: The Invincible Photographer Julia Margaret Cameron by Susan Goldman Rubin; illustrated by Bagram Ibatoulline (Candlewick, 2014) AND Imogen: The Mother of Modernism and Three Boys by Amy Novesky; illustrated by Lisa Congdon (Cameron + Company, 2012). Not one but two picture book biographies of photographers, Julia Margaret Cameron (British, 1815-79) and Imogen Cunningham (American, 1883-1976).

There. Now if anyone should ask you to name five women artists, you're all set (and then some--don't forget the illustrators of these books). Of course, you probably already were. Who's on your list?